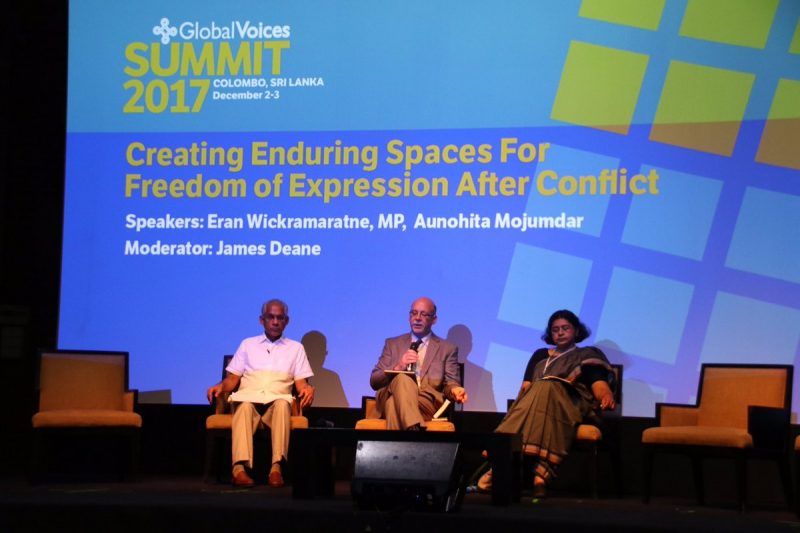

Photo by Faaris Adam, GV contributor.

Eran Wickramaratne, Sri Lankan State Minister of Finance, and Aunohita Mojumdar, Editor of Himal Southasian, will discuss freedom of expression in post-war Sri Lanka and South Asia, confronting the past, reconciliation, and the legacy of authoritarianism. How can governments engage with reform that meets the expectations of those who voted them into power? The session will be moderated by James Deane of BBC Media Action.

Jump to the start of this panel in our Livestream recording on YouTube »

« View the full list of Summit videos

Director of Policy and Learning for Media Active, BBC (and Global Voices board member) James Deane brings Sri Lanka's Minister of Finance, Eran Wickramaratne, MP and Aunohita Mojumdar, publisher of literary magazine Himal South Asia to the stage to address the topic of creating enduring spaces for freedom of expression after conflict. The minister explains that he spent the recent wave of civil war in the private sector as a banker, a much safer space than being in media or government. He became concerned that as the country moved out of war, the nation was becoming less of a republic and more of a kingdom. His friends began to urge him to consider politics, and he became the first CEO of a Sri Lankan company to become a parliamentarian.

The opposition was very small in parliament, facing a government with a 2/3rd majority. But traditional, non-government media offered space to the opposition before 2013, and since then, digital media has played a critical role in allowing the opposition to speak freely. Despite the fact that government killed journalists and led to their disappearances, media continued to provide space for essential dialog. We're over that period, he notes, though freedom is something we cannot take for granted.

Deane asks whether, in a post-truth age, we can still rely on media to help with rebuilding Sri Lanka. Minister Wickramaratne notes that “the truth will set you free”. But he notes that issues of truth come up all the time in parliament, citing an appointment where the position seeker had misrepresented his qualifications. “I have no problem with the fact that this candidate doesn't have the academic qualifications. But I have a huge problem with the fact that the credentials were misrepresented.” The issue was raised that the candidate was a war hero – the Minister noted that behavior after the war is subject to laws that behavior during war may be outside of.

The minister offers a second anecdote about truth: he visited with the chief monk of a local temple and told him the previous story. In Singhala, he told the minister “I'm advising you that collective conscience will not permit you to jail a war hero.” As an elder, he was telling him that as the minister pursues truth and justice, you need to be careful not to create more pain to society in seeking the most just outcomes.

Aunohita Mojumdar has recently been forced to move Himal from Kathmandu to Colombo, arriving only 36 hours ago. The magazine, which practices long-form, in depth journalism, spent thirty years in Kathmandu, before being forced out of Nepal. She and her team methodically searched South Asia for the best legal and fiscal venue to run the publication and discovered that Sri Lanka was the most open space in the region for open media. The magazine will now be relaunching in Colombo after a year's hiatus.

Deane notes that Sri Lanka is an an unusual democratic moment. While the rest of the world is going through a wave of nationalism, Sri Lanka appears to be on a democratic rise. He asks the minister how Sri Lanka can benefit from hewing to this democratic path. The minister notes that, if you measure political incentives in terms of the retention of power, keeping an open democracy can be a tricky path. If your desire is to have a legacy, a single-term presidency that takes the right decisions can set a country on a journey that's hard for others to reverse. The minister notes that economic prosperity tends to lead to political persistence – when the economy is bad, people vote for change.

The upcoming Sri Lankan budget goes up for vote on December 9th. There's a temptation to load up the budget with “relief” for people in the short term, but the minister notes that they're trying to steer away from populism and towards what's best for the nature in the long term.

Deane asks whether the closure of Himal is an indicator of a closing society in Nepal. The conflict is ended, democratic politics is being revitalized – why is Himal being forced out of the nation? Mojumdar notes that freedom of expression is under threat all throughout South Asia. Censorship, jailing, killings of journalists is well recorded throughout the region. But there are new sorts of threats, and we're not even measuring them. Vigilante attacks sometimes emerge from the powers that be. Governments use bureaucratic weapons to make operations impossible – that's ultimately what drove Himal out of Nepal. The technique of launching financial investigations of NGOs has a tendency to kill off vulnerable media organizations through harassment. Digital media is already so hard to sustain – if a government can constrain a publication's access to funding, it can kill off a vulnerable group.

Nepal is notably famous for community media, Deane notes. The media environment in the country is highly fragmented, but community media has been critical for democratization. Unfortunately, the ecosystem is now falling into the hands of local strongmen and public interest media is weak. Mojumdar notes that Nepali media was critical in the democratization of Nepal, much as Sri Lankan media helped with building the current post-war nation. But media that was used for reconstruction needs to hold accountable the government they helped bring to power. “We need to balance our role as journalists and activists.”

What gets attention too often, she notes, is what's hateful and hostile. We need attention to make revenue, but given that hate and anger generate attention, how do we build sustainable media that brings us together, not drives us apart?

Mojumdar wonders where the gatekeeper is in social media. “If you want to read good media, how do we make sure people can access it?” The digital space is being filled both with excellent and reprehensible media. How do we avoid being the gatekeepers and instead act effectively as curators?

Adrian from New York City identifies himself as someone who works with entrepreneurs. He wonders what business models might sustain high quality journalism in the future in emerging markets. Mojumdar notes that she has more questions than answers, and that her magazine has been sustained via donor money. When you get that donor money, you can be accused of shilling for foreign powers, no matter how independent your content is. She notes that we're willing to pay for health and education – if the government's product isn't good, we go into the private markets. We may need to face the reality that we have to pay for high quality media. “Now that online media is overtaking print media, ideas like membership models and crowdsourcing are important, but we need to be much more imaginative about them.”

Deane, who works for a public media organization, wonders whether the BBC's model of political independence for public interest media can work in the rest of the world. Is there a future for public media beyond coming from government or from foundations, which support Global Voices’ work? The minister notes that private media generally relies on public moneys as advertising. We worry sometimes that the agendas that private media takes might relate to those advertising dollars. In the digital space, he notes that membership models might be able to guarantee independence, but we should be aware that government money via advertising is likely to have an impact as well. “Maybe there are commercial ways to get government to participate. It's your job to maintain your independence.”

A question asks the Minister about “collective conscience” – how do we consider collective conscience in online spaces? The minister suggest that there may be multiple collective consciences – there's always going to be a struggle to identify what collective understanding is and should be.

Another questioner returns to Mojumdar's idea that media helps bring governments to power, then criticizes the hell of it. She wonders how the Minister is experiencing this phenomenon with Sri Lankan media. Should the government control its message more tightly? Or is this diversity of voices good for the nation, even if it makes it harder to stay in power? The minister tells a story from a village he visited yesterday – the citizens told the government that their message was very weak, that they were hearing lots of criticism of the government. The minister wondered whether they wanted him to wave the flag. He notes that there's a natural challenge for governments – people want to hear criticism, not just the government voice. In a pluralistic media, people understand that a particular media outlet often has a specific point of view – he cites the US as an example of this. “I don't know the answer, but I am opposed to government regulation of non-governmental media.” But there's a responsibility for media to report the truth and to self regulate. He notes that this debate is global, not just Sri Lanka.

Steve Butler from the Committee to Protect Journalists asks the minister for a progress update on investigations of murder and disappearances of journalists. The minister notes that he is most haunted by the murder of a journalist from the Sunday Leader, who was killed while in a secure space, likely with state involvement. Finding and prosecuting that crime is critical, even if it implicates people who are or were in power. The issue is why these investigations aren't progressing. “I don't think it's only government slowing this process. The judicial system must take responsibility… it's not unusual for a case to take 5-10 years.” In a coalition government, individuals in the government were in the former regime, and it's possible that they could be slowing things down. The public may be worried that there's a deal slowing things down – the minister rejects that.

A final questioner asks why post-conflict governments are afraid of prosecuting crimes against journalists, focusing on Nepal. Should state agencies look into freedom of expression regarding communal offenses? Mojumdar notes that state officials were a party to the conflict and to actions taken during war. There seems to be a tacit agreement not to pursue war crimes. In Sri Lanka, she speculates, many of the perpetrators of war crimes are the current military, which makes it very hard to prosecute these crimes.

Deane notes, as a corrective, that the judicial process in Nepal may be working regarding Himal. Mojumdar notes that the chief justice did act against a public prosecutor, but she now faces criticism herself for taking too many actions on Himal's basis. Rule of law is not yet established well enough to count on it.