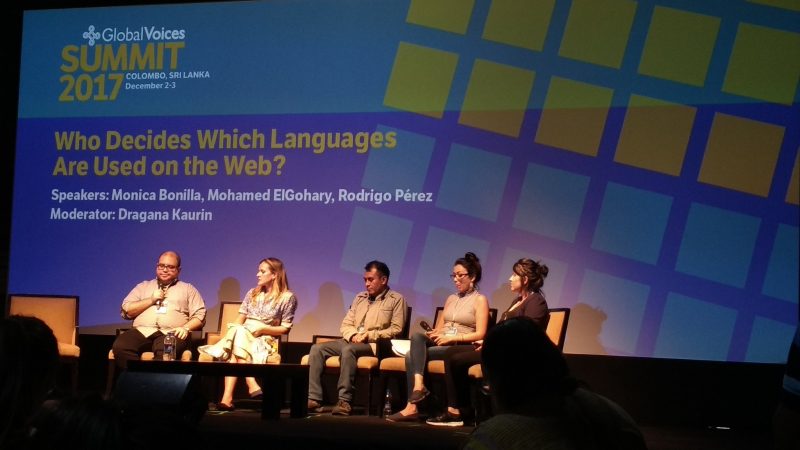

Great opening from panel facilitator @draganakaurin at #GV2017 in #srilanka: “say there's a sign in #sinhala here outside saying ‘free chocolate’. If you don't read #sinhala you won't get any & you'll get pretty angry. Because chocolate should be for everyone, just like Internet”. Photo by Gwenaelle Lefeuvre [1].

(Monica Bonilla and Rodrigo Perez speak Spanish during this panel presentation with interpretation from Andrea Chong-Bras, a Global Voices subeditor and Spanish/English translator.)

Jump to the start of this panel in our Livestream recording on YouTube » [2]

« View the full list of Summit videos [3]

Who gets to decide what languages get spoken online? Sometimes countries pass laws about which languages need support, and sometimes online platforms make decisions. But that's not always fair for people who use these tools.

Dragana Kaurin, the moderator of this session, started the conversation by pointing out that in Canada, labels need to be in English and French so as not to marginalize the Quebecois. But what about the Objibwe or the Cree?

Mohamed ElGohary, the Global Voices Lingua [4] Director, is interested in how tech tools support languages. When platforms decide not to support a language, it's very hard for users to meaningfully use that tool. Sometimes Silicon Valley doesn't see the potential value of its users. Other barriers come up as well: programming languages are in English, and those who don't speak the language comfortably have an additional hurdle to learning that program.

Rodrigo Perez is a Zapotec speaker, one of the indigenous languages of Mexico. Approximately 400,000 people speak the language, but his variant is spoken by about 4,000 people. The language is discriminated against in Mexico, but his dialect is one of the first appearing online due to his activism. Of the 68 original indigenous peoples of Mexico, 40% are in danger of disappearing in the next two decades.

Monica Bonilla works on localization projects in Colombia, including Mozilla Firefox. Approximately 65-68 indigenous languages exist in Colombia, and all of them are threatened. Bonilla has worked in Mexico and Paraguay with indigenous communities, and while she's not a speaker of an indigenous language, the struggles around those languages are central to her work.

ElGohary makes the point that software developers are rarely speakers of smaller languages. People who speak those languages don't have a good channel to give feedback to companies about the need for language support. He would like to see companies lean on advances in machine translation to make it possible for more people around the world to learn and create using these tools. Kaurin explains that it's a lot easier to do this with free software.

Perez encountered the internet for the first time 15 years ago. He opened up Netscape Explorer, saw it was in English and concluded:

The internet is not for me.

It took Perez five years to come back and find interfaces that were in Spanish. Ten years later, he found free source software that wasn't just in Spanish, but in Catalan and other minority languages. He thought,

If this is in Catalan, why can't it be in Zapotec? Aren't English, Spanish and Zapotec all equal languages?

So he began bringing Zapotec into Firefox for Android, Firefox Desktop, and other platforms. He's now working on becoming a Zapotec Youtuber and writing Zapotec poetry online.

What would happen if everything that was in English and Spanish was now in Zapotec?

This has been difficult and filled with obstacles, but it's all been about bringing Zapotec online.

The tyranny of written language

There is tyranny in the written word. They made us believe that that the only way to keep knowledge was through written word. – Rodriguez Perez #GV2017 [5] pic.twitter.com/zZac6XKckj [6]

— Pru Nyamishana (@nyapru1) December 3, 2017 [7]

Kaurin asks why Perez wanted to work on free software rather than on translating books. He explains that there's a tyranny of written language.

Developers want us to think [written language] the only way to express ourselves. It's not true

The majority of indigenous languages are oral languages. This is a great opportunity for the internet because it's multimedia — it supports video, audio, and images as well as text. It's easier and better to use indigenous languages online than in written form.

Bonilla notes many limiting factors when using different languages online. One key barrier is that software designers see the written language as primary. A major barrier in Colombia to internet use is literacy. Another is language. In academic research, the vast majority is in English. In Colombia, Spanish is the official language, but in each territory, there's an indigenous language as an official language. But in practice, people need to learn English and Spanish.

Bonilla explains that she usually begins working with communities face-to-face. But the telephone and the internet allows them to remain in contact and continue the relationship. This communication helps us break the idea that the internet is why we aren't speaking some of these languages — instead, the internet may be what helps us learn to speak these languages.

Digital language activists find online allies

Ten years into his work, Perez is now working on helping other activists work on the future of language online. There's a set of allies — Wikipedia, Mozilla and Global Voices — who are excited about this form of digital activism.

Gohary explains that Rising Voices works with indigenous communities to help represent underrepresented languages online, working on much the same mission as organizations like Wikipedia, and learning from their models. Gohary laments how many commercial companies ignore the importance of language. Either they use volunteers to do their translations or rely on Google Translate. In the process, they're sacrificing huge potential markets. Western companies appear to understand that there's a Chinese market, but don't invest in localizing tech for markets in Arabic, for example.

Perez notes that one of the greatest advantages of free software is that anyone can build it. Still, there's an economic price associated with building that software. The person designing the software still has to live. Free software isn't free of cost, at least not to the developer. We need to donate so that these programs can continue to exist. Users need to keep in mind that there's a real cost to these tools.

“If it's private, I'm shut out — if it's free software, I can put Zapotec on it.”

The future of languages online

Gohary points to a future of multilingual developers who speak so many languages that someone working on issues related to the Burmese language in a program are actually native Burmese speakers. We're far from that reality, but it would help overcome the barriers of communication between language experts and programmers today.

Perez wants to ensure the Internet reaches every single person, including those who don't speak popular languages.

“We've overcome technical challenges in the past — we can continue the fight for a multilingual space where everyone is represented and everyone has a voice.”

But former Global Voices managing editor Solana Larsen wonders whether there's a contradiction in wanting to ensure massive platforms are multilingual and concerns about digital colonialization. Should we be looking instead for local platforms, not universal ones? Is there a danger of making these platforms more powerful? Gohary sees the language barrier as so significant that the real problem of access may outweigh the more theoretical problems of digital imperialism.

Perez notes that since he started his work, he's been an advocate for free software:

“Getting money isn't the objective. We want people to be completely free to decide what tools they can use. If Facebook does a translation into Maya, behind the scenes, it means you're connected to them. We need to promote software that promotes freedom and avoid private platforms as much as possible.”

Bonilla remembers that a member of an indigenous community told her once that speaking an indigenous language is a form of resistance. Writing in that language online is also a form of resistance. Telling the world that a person who speaks an indigenous language exists is a form of resistance.